(EN) Peut-il y avoir à nouveau une crise financière ?

This article was written at the beginning of March, before the coronavirus epidemic reached thehealth, economic and financialproportions we are currently experiencing .

This article was written at the beginning of March, before the coronavirus epidemic reached thehealth, economic and financialproportions we arecurrently experiencing.Thearticle envisages a financialcrisisoriginating in finance itself, or in the evolution of oil prices, and not in an " exogenous" cause .As theexcesses ofindebtedness mentioned by the author areset tointensify in the wake of the health crisis, the question of the outbreak ofa financialcrisiswill doubtless become topicalagain at a laterdate.

***

Financial crises (in Japan in 1990, and in the USA and Europe in 2000 and 2008) are systematically linked to rising interest rates, high levels of debt and asset price bubbles. Hence the concern in OECD countries, as well as in China and emerging countries, about high debt levels and the return of bubbles. For the time being, however, very low interest rates are preventing a crisis from breaking out. This brings us to the central question: why are interest rates so low today? There are both structural reasons (rising savings rates, excess demand for risk-free debt) and a reason linked to the absence of inflation, i.e. the maintenance of highly expansionary monetary policies.

Could inflation then return, pushing up interest rates and triggering a financial crisis? There are two main reasons for the absence of inflation today: wage austerity, which in many countries is distorting income distribution to the detriment of wage earners; low energy prices, which are surprisingly low after many years of growth. Could we then see a return to inflation with the implementation of different labor market policies?

Finally, the question remains: can a financial crisis be triggered even if inflation doesn't return? This is already the case in many emerging countries, where international capital flows and exchange rates are highly variable. For OECD countries, the question is whether financial imbalances (bubbles, liquidity risk taken on by investors) can trigger a crisis even without a rise in interest rates, and whether there can be a crisis without a rise in inflation.For OECD countries, the question is whether financial imbalances (bubbles, liquidity risk taken by investors) can trigger a crisis even without interest rate rises, and whether there can be a self-fulfilling public debt crisis (anticipation of the crisis causes interest rates to rise, triggering the crisis).

THE STRUCTURE OF FINANCIAL CRISES IS ALWAYS THE SAME

In Japan in 1990, in the eurozone and in the United States in 2000 and 2008, the financial crises were all linked to rising interest rates, at a time when private sector debt levels were high and asset prices (real estate, financial) had risen sharply.

Rising interest rates trigger two self-perpetuating mechanisms: loss of borrower solvency, falling asset prices and negative wealth effects.

The result was a sharp fall in demand and a sharp rise in borrower defaults, leading to recession and crisis.

WHICH EXPLAINS THE CONCERN WE FEEL TODAY.

Concerns about the risk of a financial crisis recurring stem from the fact that debt levels are very high today, both in OECD countries and in China and emerging countries.

But the fact that short and long-term interest rates have remained at extremely low levels means that there is no financial crisis or serious loss of solvency among borrowers today). With interest rates so low, the vast majority of borrowers remain solvent, even with such high levels of debt.

But a rise in interest rates could lead to a loss of solvency for many borrowers as interest payments on their debts rise.

HENCE THE IMPORTANT QUESTION: WHERE DO TODAY'S LOW INTEREST RATES COME FROM?

There are two types of explanation for low interest rates.

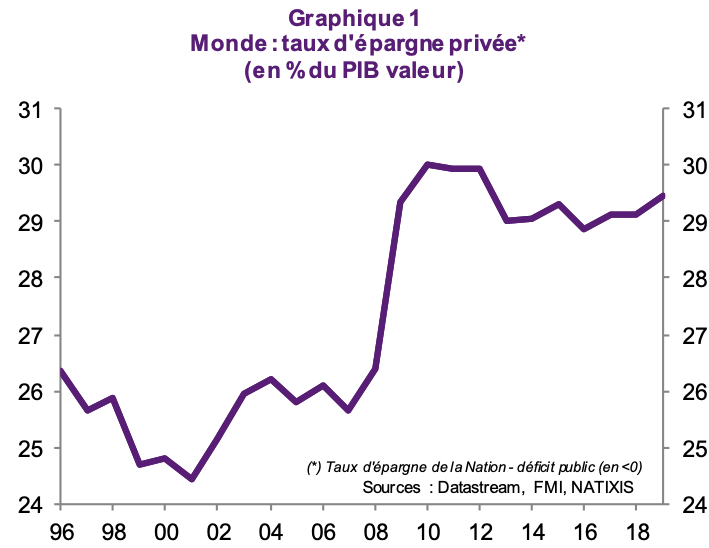

The first is that there are structural reasons: in particular, the rise in the world's private savings rate (graph1, resulting in low equilibrium real interest rates); the excess demand for risk-free debt (in particular for the supposedly risk-free public debt of OECD countries[1]), with a high level of aversion to the risk of default.s of demand for risk-free debt (in particular for the supposedly risk-free public debt of OECD countries[1]), with investors' average level of risk aversion high since the 2008 crisis.

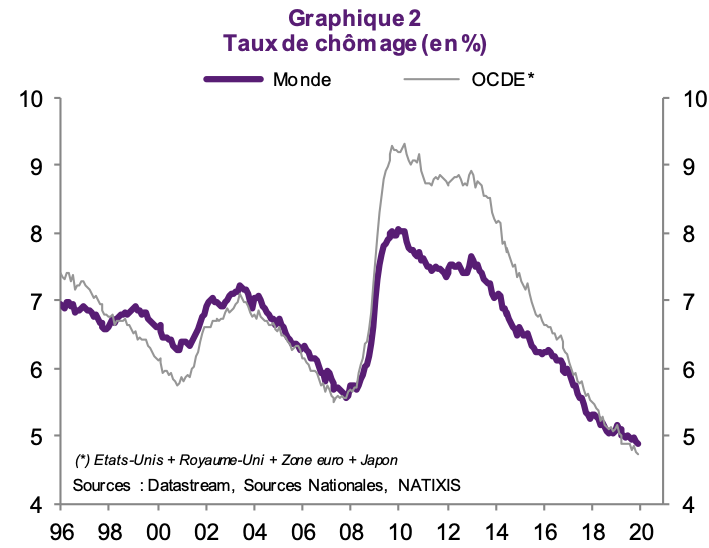

The second explanation relates to expansionary monetary policies, which are linked to low underlying inflation in both OECD and emerging countries. Low inflation has enabled central banks to keep interest rates very low, even as unemployment rates have fallen to very low levels (graph 2).

HENCE THE CENTRAL QUESTION: COULD INFLATION RETURN?

Today, we're seeing a major weakening of Phillips curves, i.e. of the relationship between the business cycle and inflation. What are the two main causes of the major weakening of Phillips curve effects in recent times?

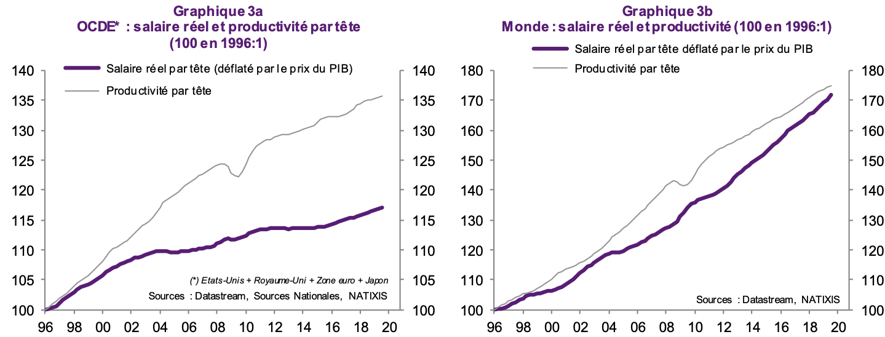

The first is wage austerity: in the vast majority of countries, real wages are growing at a slower pace than labor productivity, and income distribution is distorted to the detriment of wage earners (graphs 3a/3b).

This abnormally low level of wages and labor costs, which persists even when the unemployment rate becomes very low, explains the absence of inflation in the recent period.

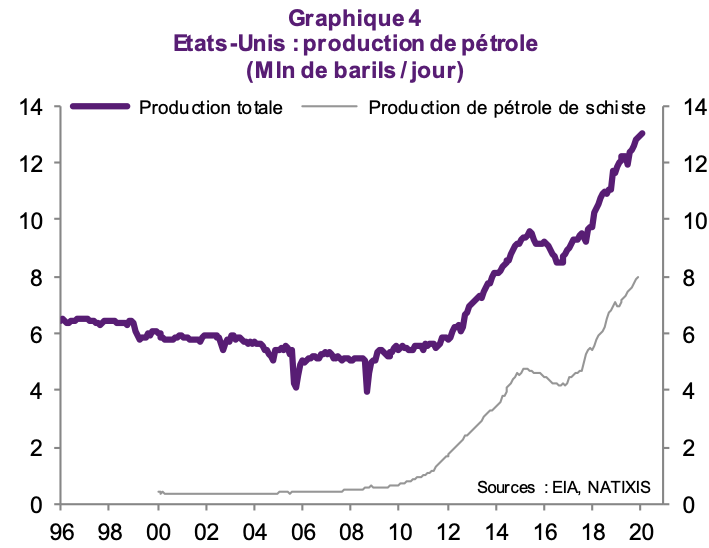

The second reason for the absence of inflation in the recent period is that the price of oil has remained low, whereas in the past it used to rise at the end of expansionary periods.

This lack of reaction of oil prices to growth is essentially due to the sharp rise in oil production in the United States with the emergence of shale oil (graph 4).

The risk is therefore essentially that of a change in the way the labor market operates, with a return to higher wage increases. The triggering factor would be a political change, with the arrival in power of a political party pursuing a wage policy more favorable to employees (a sharp rise in the minimum wage, for example). This could be the case in the USA as early as 2021, should a left-wing Democrat win the presidential election.

CAN THERE BE A FINANCIAL CRISIS WITHOUT A RETURN TO INFLATION?

The return of inflation, probably also due to a major change in labor market policies, would trigger a financial crisis, with the induced rise in interest rates and its effect on both borrowers' solvency and financial asset prices.

But can we envisage a less simple situation where a financial crisis is triggered even in the absence of a return to inflation?

The first possibility is that low interest rates generate financial imbalances that lead to a crisis, even in the absence of rising interest rates.

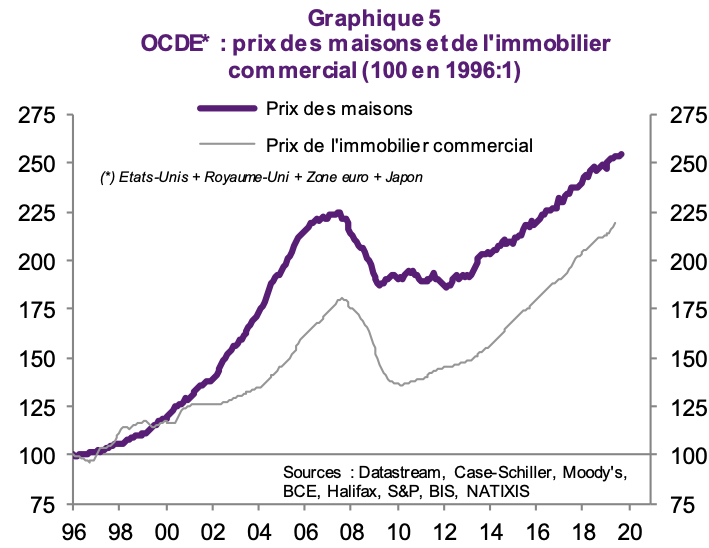

Today, OECD countries are witnessing a sharp rise in real estate prices (graph 5) and, with long-term interest rates very low, a growing shift by investors towards illiquid assets (so-called "real" assets) such as real estate, private equity, infrastructure and CLOs (securitized loans).low long-term interest rates, investors are increasingly turning to illiquid assets (so-called "real" assets) such as real estate,private equity, infrastructure and CLOs (credit securitization).

This in itself can trigger a crisis without raising interest rates: the real estate bubble can burst, simply because real estate prices are abnormally high and house purchases plummet; an accidental rise in risk aversion, due for example to a geopolitical crisis, can cause savers to withdraw and imply that investors are faced with outflows when their assets are illiquid.an accidental rise in risk aversion, due to a geopolitical crisis for example, can cause savers to withdraw, meaning that investors are faced with outflows of funds when their assets are illiquid and therefore difficult to sell, resulting in an illiquidity crisis.

The second possibility of triggering a financial crisis without a rise in interest rates is the appearance of a self-fulfilling crisis, particularly on public debt.

If investors anticipate the risk of a government default, this anticipation pushes up interest rates, and the rise in interest rates brings out the risk of default, which it was therefore rational to anticipate. This type of self-fulfilling crisis was observed from 2010 to 2014 in the peripheral countries of the eurozone, with rising interest payments on debt due to the rise in interest rates.This type of self-fulfilling crisis was observed in the peripheral countries of the eurozone, with rising interest payments on debt due to the rise in interest rates resulting from the expectation that these countries would default.

SUMMARY: WE COULD ARGUE THAT A FINANCIAL CRISIS IS INEVITABLE

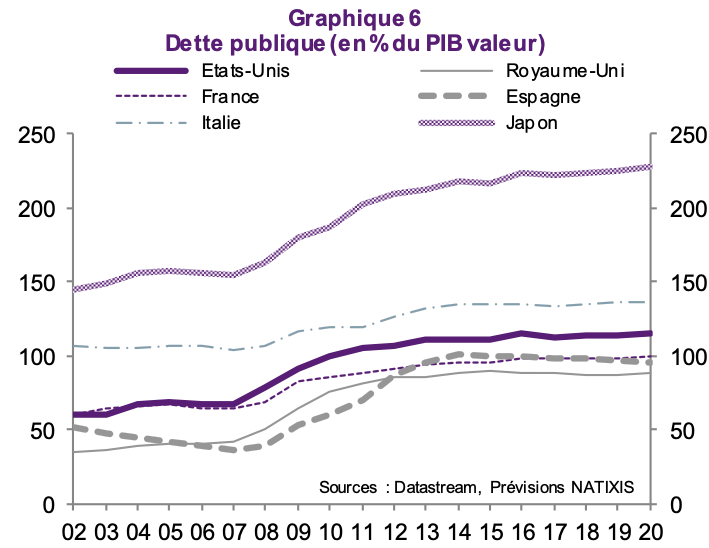

Either inflation returns, with a change in labor market policies in the major OECD countries, and the induced rise in interest rates leads to a crisis with high debt levels and asset prices. Or inflation does not return, and the financial imbalances induced by maintaining low interest rates (real estate bubbles, investment in illiquid assets, rising public debt in many countries, graph 6) also eventually lead to a crisis. Whether or not inflation returns, there will be a financial crisis in the future.

No comment

Log in to post comment. Log in.